PLEASE CLICK HERE TO SEE MORE IMAGES OF SOUNDWAVES

18th May - 29th June 2007Kinetica Museum, Spitalfields Market, London, UK

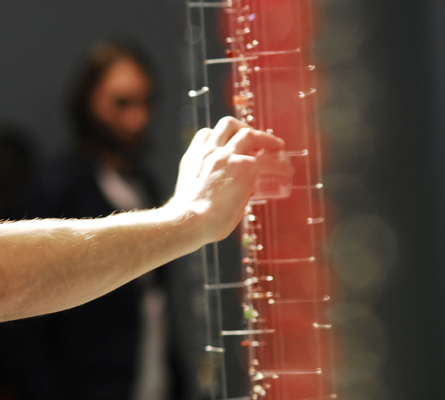

This major exhibition focused on artworks that explore, warp, collect and manipulate sound. It was curated by Kinetica Museum, in our old museum space in Spitalfields market, London. In collaboration with Cybersonica Festival, this six week show presented the work of more than fifteen prominent and pioneering U.K and European artists, and featured four new commisssions funded by the Arts Council England.

Alongside the exhibition there was a programme of presentations and talks, delving further into the exploration of sound and aural experiences. Contributors included: Jake Ewen's presentation 'Cymatic planet'; a presentation by Alex Zivanovic on the work of pioneering artist/engineer Edward Ihnatowicz - creator of the Senster and S.A.M - the first Sound Automated Machine, first shown at Cybernetic Serendipity 1969 ICA; a discussion on audio modification by Brian Duffy and DJ Tendraw & The Gypsies Dog; and a talk by Rolf Gehlhaar - inventor of Sound:Space.

One can look at seeing; one can’t hear hearing. Marcel Duchamp - 1914

And sound, somewhere between a stuff and a non-stuff, a species of air or type of object so fast, fluid, dispersed yet invisible that we treat it as an event sharing common qualities with thought, pain, time, cloud formations; a blow to the side of the head delivered by the kind of ‘sap’ seen in film noir pictures of the 1940s; unseen electrical energy that can nevertheless send a person flying across a room; the way that breath differs coming back in to the body, to breath just expelled (particularly when directed at glass and sounded out or sucked audibly in); movement through the scent of woodland after rain or the stink of the city in August; the taste of water; whatever it is that happens when sexual stimulation, tickling or sneezing takes place, and a memory of heightened moments from a very long time ago.

Because sound is mysterious, elusive, even wilfully eccentric in its behaviour, we may come to believe that it possesses as much life as a human, a frog or a plant (but then this question of life is complex, since a Japanese gardener will ask a rock where it would like to be placed). On a virtually windless day when the weather is dry, a faint high crackle emanates from that woodland floor that we absorbed through our nostrils in wetter conditions; the sound itself seems to be a spoken text, indecipherable of course, redolent of chaotic automatic calligraphy, a whispering book that by-passes the word and simply issues outward, a process without agency. That may be how it seems, and some of our fascination with automata, artificial life, robotics and the uncanny qualities of machines lies within this supernaturalist imagining of nonsentient phenomena acquiring life.

Sound moves in waves. We can see a visual representation of this movement in photographic studies of periodicity made by the Swiss scientist Hans Jenny in the 1960s. These were inspired by the work of Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni, whose paper entitled ‘Discoveries In the Theory of Sound’ (1787), documented a method of rendering sound as a visible phenomenon. Chladni sprinkled sand on a sounding body such as a metal plate then observed the patterns formed as “sand is thrown off from the vibrating portions of the surface, often with considerable violence, whereas it remains at rest on the places where there is no motion.” By subjecting objects and substances to pure tones and oscillations Jenny used a comparable technique, but expanded his materials to include liquids, gases, powders, pastes, soap bubbles, mercury and Lycopodium spores of club moss. The resulting photographs (isolated from any knowledge of their source these could be mistaken for moonscapes, the cosmic diagrams of Tantrism, or psychedelic visions), are a monstrously beautiful reminder of the physiological impact of sound on the human body. Cymatics, Jenny called his study, after kyma, Greek, the wave. One can see hearing, yet still not hear hearing.

Out of the emerging and difficult understanding that sound was vibration caused by invisible waves came a wealth of inventions, a web of connections. Charles Babbage, inventor of a calculating machine, the Difference Engine, believed that vocal pulsations were inscribed for eternity into the atmosphere of the earth, as if the earth were a phonographic archive of vast dimensions. Alexander Graham Bell encouraged hearing-impaired children in Boston to hold balloons in their hands when walking in the streets. Horse-drawn wagons, silent to them so a threat to their safety, could be heard as vibration, transmitted up from cobblestones through the balloon and into the child’s hands. Later he experimented on the family dog, Bell persuading the dog to growl, then by moving its larynx as his brother changed the shape of its lips, he produced sounds that corresponded to human words.

Along with these experiments, Bell’s invention of the telephone was also influenced by the notorious Turkish chess player, the hookahsmoking automaton that appeared to be a master of chess. Bell had seen a version of the chess player constructed by Charles Wheatstone in 1838, but there was a longer history. The original machine was invented in Austria by Wolfgang von Kempelen and built in 1769. An intricate web issues from this device of deception, traced by Mladen Dolar in his book, ‘A Voice and Nothing More’: the American tour of the chess player organized by Johann Mälzel after Kempelen’s death; Edgar Allan Poe’s detective research into the mystery of the machine, detailed in his 1836 essay, ‘Maelzel’s Chess-Player’; Mälzel’s role in the construction of both the first metronome and Beethoven’s hearing aid, Beethoven being the first composer to use a metronome tempo indication in a score, and preceding all of this, the strange horror induced by Kempelen’s invention of a speaking machine. Kempelen published a book which described this latter machine in great detail. “Yet, no matter how much the thing was described for everybody to study,” writes Dolar, “the machine nevertheless kept producing effects which can only be described with the Freudian word ‘uncanny’.”

In the midst of all these interweavings is a sense of second life, a point where senses and perceptions are no longer as unambiguous and distinct as we might wish, but also a growing unease as each of these inventions raises a challenge to the status of humankind. The android, the metronome, the hearing aid, the calculating machine, the telephone, all simultaneously expand human potential, accede to human frailty, worry at death and its inevitability. Poe made an explicit comparison between the Turkish chess player (of which, correctly, he was sceptical) and Charles Babbage’s calculating machine, asking “What shall we think of a machine which can not only accomplish all this, but actually print out its elaborate results, when obtained, without the slightest intervention of the intellect of man?” Perhaps Poe was unaware of the prediction by Babbage’s collaborator, Lady Lovelace, who in 1843 published speculative ideas about a machine of the future that might play complex music programmed by a composer. This machine would be incapable of autonomous creation, she believed, for it would depend upon the “intellect of man” (or woman).

Techno-fear, arising as a question in Poe’s text, was expressed pungently – a fragmented, bitter rant – by William Gaddis in his final novel, ‘Agape Agape’, published in 2002. This records the incoherent, semi-autobiographical interior monologue of a dying man who blames the player piano, and all other examples of automation, for contemporary alienation and commodification. For him, the mechanisation of music is at the heart (and absent soul) of the modern disease: “. . . no match for the march of science that made it possible, marches right on and leaves it in the dust, pianos nobody can play and millions of piano rolls left in the dust while their splendid phantom hands are pushed further from reach by the gramophone and finally paralyzed by the radio teaching birds to sing birdsongs O God, O God, O God…”

In his emphysemic last gasp, Gaddis wrote this novel as an acknowledgement that his great overarching research project into mechanisation, automation and player piano history would never be turned into a coherent study, so leaving behind a mass of research into time/motion studies, punch cards, Jacquard’s loom, and the entire unfathomable tangle of imprisonment systems, the textile industry, artificial animals, the assembly line, mass produced art, machine rhythms, the computer and where does it stop? His repetition of the suggestive phrase, “phantom hands”, says it all, yet reminds us of the compensations for this supposed alienation, the ghost world in which machines perform human work, or behave as humans who are less or more than humans; reminds us of horror films in which severed hands can play a musical instrument; reminds us the maniac manic prose of Kenji Siratori, its ceaseless repetitions of replication and the transformation of the retro-Adam into code; or of the creeping half-human worlds of the Quay Brothers, Raymond Roussel, Hans Bellmer, or Tipu’s Tiger. The latter, housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum and created by Tipu Sultan, a fervent enemy of British imperialists, was captured by the British army in 1799. A large sculpture of a tiger devouring a European, the ‘instrument’ housed an organ which, when cranked by a handle, approximated the sound of a prostrate suffering man being gnawed by a growling tiger. Comparisons with Alexander Graham Bell and the manipulated sounds of the family dog are perhaps inevitable.

Phantom hands also direct us to a world in which the mystical aether, the spirit world of 19th century technology has evaporated finally, enabling machines to be transparently machines and revealing the hidden forces of phenomena – electricity, magnetism, wave forms, the apparent randomness of chaotic patterns and those signals which function beyond the sensory ranges of human beings – as sufficiently poetic in their uncovered and celebrated reality to discard mystical projection.

Through movement in sound art (the kinetic), any artificial separation of senses is questioned. They are different, yes, but for those of us who are not deprived of vision, hearing, or any other senses or capacities, to walk is a passing through sound, scent, visual images, skin sensations, all impressions that in turn pass through us, merge into shadows of each other, become indistinguishable, mutate as the environment changes, work upon us at levels that are pure sensation, subliminal impression and a becoming of conscious thought. Underneath all of this, there is the faintest awareness of noises that are barely audible, images at the edge of vision, fluctuations of temperature, scents too faint to catch for more than a moment, light and sound waves too rapid, too transient, too subtle to be caught or stilled.

ARTISTS

Pierre Bastien Arcángel Constantini Max Eastley Julie Freeman Andy Huntington Lu Clarke and Jaye Ho Martin Hesselmeier and Karin Lingnau Michael Markert Gavin Morris Rob Mullender Martin Riches Spaceman Technologies Peter Vogel